In an otherwise excellent article for the Sunday Telegraph last week about our government’s hopeless pandemic response, Dan Hannan made one comment I’d like to take issue with. He wrote: ‘For years to come, Britain will be poor, indebted and repressive because, in early March 2020, no one (with the exception of one brave Sunday Telegraph columnist, modesty forbids, etc) wanted to stand in the way of a stampede.’

In fact, he wasn’t the only one and, lacking Dan’s modesty, I’m happy to name myself as one of the first journalists to oppose the lockdown policy, along with Peter Hitchens, Allison Pearson, Ross Clark, Julia Hartley-Brewer and a handful of others. But Dan is right to emphasise how one-sided the debate was, with almost everyone falling in behind the government. He singles out human-rights lawyers as missing in action, given that this was ‘the greatest interference with personal liberty in our history’ (Jonathan Sumption), and we can add the ‘neo-republican’ political theorists who champion the Roman conception of liberty as self-rule, such as Quentin Skinner and Philip Pettit. Both those intellectual giants defended the policy.

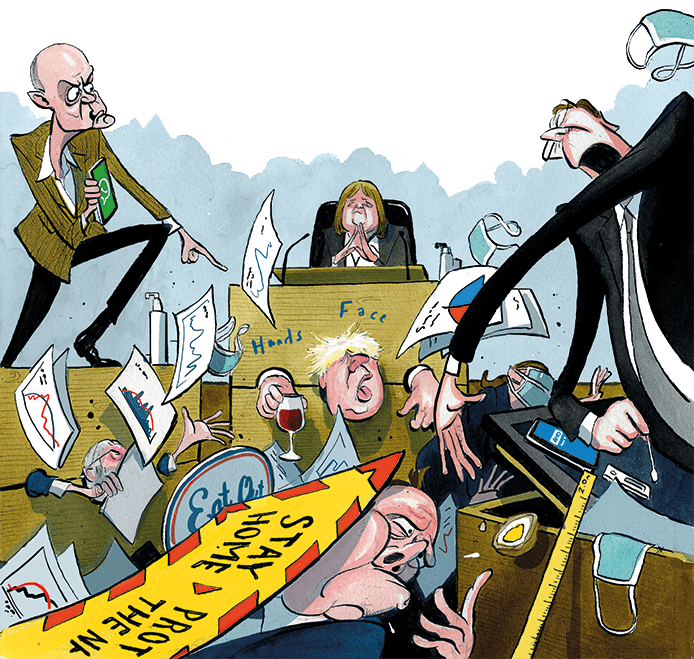

I thought I could count on the Tufton Street mafia to weigh in on my side – after all, aren’t they wedded to the principle that ‘government is best that governs least’? Surely, paying people not to work, forcing businesses to close and increasing public expenditure by £400 billion was anathema to them? But most of the right-wing policy wonks became enthusiastic supporters of the Covid restrictions, a group I dubbed ‘libertarians for lockdown’. Boris Johnson passed the initial test with flying colours, urging the public to ‘take it on the chin’, but soon fell into lockstep with the more cautious people surrounding him, including my political lodestars Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings. As someone who’d shared foxholes with them during the Brexit wars, that was heartbreaking.

I’d like to say all these people now recognise the error of their ways and come bounding up to me at parties to tell me how right I was, but as Mark Twain said: ‘It’s easier to fool people than convince them that they have been fooled.’ The only person I’ve received any kind of mea culpa from is Boris, who sheepishly told me at the end of a long evening last year that I may have been right about lockdown. At least, I think that’s what he said. As friends of his will know, he rarely looks you in the eye and half-mumbles, half-gabbles when admitting to a mistake, so I may have misheard. I give him credit for standing his ground in December 2021, refusing to cancel Christmas, and I’ve no doubt Sir Keir Starmer’s response to the pandemic would have been worse.

As Mark Twain said: ‘It’s easier to fool people than convince them that they have been fooled’

I was initially sceptical about the official Covid Inquiry, worried that Baroness Hallett had already made up her mind that we should have locked down sooner and harder. But after seeing her Module 1 report, which was more nuanced than I’d anticipated, I’m optimistic she’ll condemn some aspects of the lockdown policy, such as the decision to close schools. On the other hand, I don’t think it matters very much what she concludes, because a future government, when faced with another pandemic, will just ditch all our carefully laid plans and do whatever is politically expedient, like the Conservatives did in 2020. The influenza pandemic preparedness strategy, which cautioned against locking down, was unceremoniously dumped within weeks on the grounds that it was designed to manage an outbreak of bad flu rather than something more serious. In fact, the fatality rate of Covid-19 was comparable with that of the Hong Kong flu pandemic of 1968-70. Sweden, which did follow our strategy, experienced fewer Covid deaths per capita than us.

But I’ve decided to forgive the poor decisions made by the politicians in charge when the pandemic struck, because their room for manoeuvre was constrained by the public’s limited appetite for risk. They might now accept that locking down caused more harm than it prevented, but still argue they had no choice because there was just a chance that if they’d stuck with Boris’s ‘squash the sombrero’ strategy millions would have died. They knew the people who had elected them prized their own safety above their liberty and, if they had been asked how to respond to a low-probability, high-consequence risk, they would have urged the politicians to do everything in their power to mitigate it. Sweden was able to do the right thing because Anders Tegnell, who was in charge of health policy, was a bureaucrat with an unusual degree of autonomy. And for once, a deep state official made the right call.

Comments